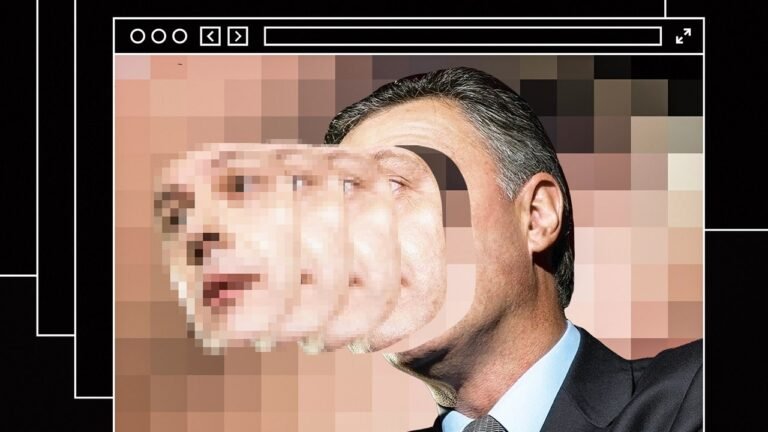

“There’s a video of Gal Gadot having intercourse along with her stepbrother on the web.” With that sentence, written by the journalist Samantha Cole for the tech web site Motherboard in December, 2017, a queasy new chapter in our cultural historical past opened. A programmer calling himself “deepfakes” instructed Cole that he’d used synthetic intelligence to insert Gadot’s face right into a pornographic video. And he’d made others: clips altered to characteristic Aubrey Plaza, Scarlett Johansson, Maisie Williams, and Taylor Swift.

Porn, as a Instances headline as soon as proclaimed, is the “low-slung engine of progress.” It may be credited with the fast unfold of VCRs, cable, and the Web—and with a number of necessary Internet applied sciences. Would deepfakes, because the manipulated movies got here to be identified, be pornographers’ subsequent technological present to the world? Months after Cole’s article, a clip appeared on-line of Barack Obama calling Donald Trump “a complete and full dipshit.” On the finish of the video, the trick was revealed. It was the comic Jordan Peele’s voice; A.I. had been used to show Obama right into a digital puppet.

The implications, to these paying consideration, had been horrifying. Such movies heralded the “coming infocalypse,” as Nina Schick, an A.I. skilled, warned, or the “collapse of actuality,” as Franklin Foer wrote in The Atlantic. Congress held hearings concerning the potential electoral penalties. “Suppose forward to 2020 and past,” Consultant Adam Schiff urged; it wasn’t laborious to think about “nightmarish eventualities that would go away the federal government, the media, and the general public struggling to discern what’s actual.”

As Schiff noticed, the hazard wasn’t solely disinformation. Media manipulation is liable to taint all audiovisual proof, as a result of even an genuine recording could be dismissed as rigged. The authorized students Bobby Chesney and Danielle Citron name this the “liar’s dividend” and observe its use by Trump, who excels at disregarding inconvenient truths as pretend information. When an “Entry Hollywood” tape of Trump boasting about committing sexual assault emerged, he apologized (“I mentioned it, I used to be unsuitable”), however later dismissed the tape as having been faked. “One of many biggest of all phrases I’ve provide you with is ‘pretend,’ ” he has mentioned. “I suppose different individuals have used it, maybe over time, however I’ve by no means seen it.”

Deepfakes débuted within the first 12 months of Trump’s Presidency and have been bettering swiftly since. Though the Gal Gadot clip was too glitchy to go for actual, work executed by amateurs can now rival costly C.G.I. results from Hollywood studios. And manipulated movies are proliferating. A monitoring group, Sensity, counted eighty-five thousand deepfakes on-line in December, 2020; lately, Wired tallied almost thrice that quantity. Followers of “Seinfeld” can watch Jerry spliced convincingly into the movie “Pulp Fiction,” Kramer delivering a monologue with the face and the voice of Arnold Schwarzenegger, and so, a lot Elaine porn.

There’s a small educational discipline, referred to as media forensics, that seeks to fight these fakes. However it’s “combating a dropping battle,” a number one researcher, Hany Farid, has warned. Final 12 months, Farid printed a paper with the psychologist Sophie J. Nightingale exhibiting that a synthetic neural community is ready to concoct faces that neither people nor computer systems can determine as simulated. Ominously, individuals discovered these artificial faces to be reliable; actually, we belief the “common” faces that A.I. generates greater than the irregular ones that nature does.

That is particularly worrisome given different tendencies. Social media’s algorithmic filters are permitting separate teams to inhabit almost separate realities. Stark polarization, in the meantime, is giving rise to a no-holds-barred politics. We’re more and more getting our information from video clips, and doctoring these clips has develop into alarmingly easy. The desk is about for disaster.

And but the visitor has not arrived. Sensity conceded in 2021 that deepfakes had had no “tangible affect” on the 2020 Presidential election. It discovered no occasion of “dangerous actors” spreading disinformation with deepfakes wherever. Two years later, it’s simple to seek out movies that exhibit the terrifying prospects of A.I. It’s simply laborious to level to a convincing deepfake that has misled individuals in any consequential means.

The pc scientist Walter J. Scheirer has labored in media forensics for years. He understands greater than most how these new applied sciences may set off a society-wide epistemic meltdown, but he sees no indicators that they’re doing so. Doctored movies on-line delight, taunt, jolt, menace, arouse, and amuse, however they not often deceive. As Scheirer argues in his new guide, “A Historical past of Pretend Issues on the Web” (Stanford), the scenario simply isn’t as dangerous because it appears to be like.

There’s something daring, maybe reckless, in preaching serenity from the volcano’s edge. However, as Scheirer factors out, the doctored-evidence drawback isn’t new. Our oldest types of recording—storytelling, writing, and portray—are laughably simple to hack. We’ve needed to discover methods to belief them nonetheless.

It wasn’t till the nineteenth century that humanity developed an evidentiary medium that in itself impressed confidence: pictures. A digital camera, it appeared, didn’t interpret its environment however registered their bodily properties, the best way a thermometer or a scale would. This made {a photograph} basically not like a portray. It was, in keeping with Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., a “mirror with a reminiscence.”

Truly, the photographer’s artwork was just like the mortician’s, in that producing a true-to-life object required lots of unseemly backstage work with chemical compounds. In “Faking It” (2012), Mia Fineman, a pictures curator on the Metropolitan Museum of Artwork, explains that early cameras had a tough time capturing landscapes—both the sky was washed out or the bottom was laborious to see. To compensate, photographers added clouds by hand, or they mixed the sky from one unfavorable with the land from one other (which is likely to be of a special location). It didn’t cease there: nineteenth-century photographers typically handled their negatives as first drafts, to be corrected, reordered, or overwritten as wanted. Solely by enhancing may they escape what the English photographer Henry Peach Robinson referred to as the “tyranny of the lens.”